MY SECRET FEMINIST AGENDA

These are a collection of my thoughts on how women are represented in art and the media. The sources I used to educate myself have been linked within the essay for further reference. Let me know your thoughts on this issue, I’d love to chat.

“I’m a feminist because I can’t live in a world where I am defined, limited, and categorized by my genitalia, where women are objectified beyond reason, where rape culture thrives, and where these injustices (and more) are so blatantly ignored and denied by so many people.”

– Liora K. Baker

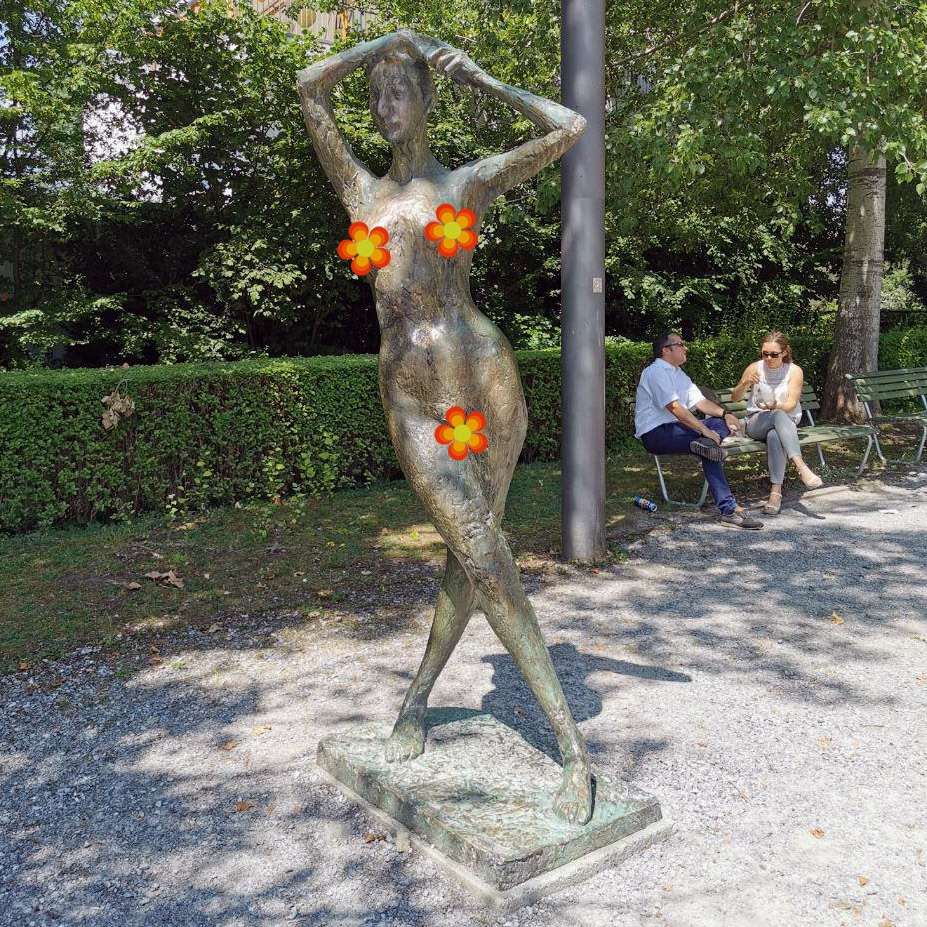

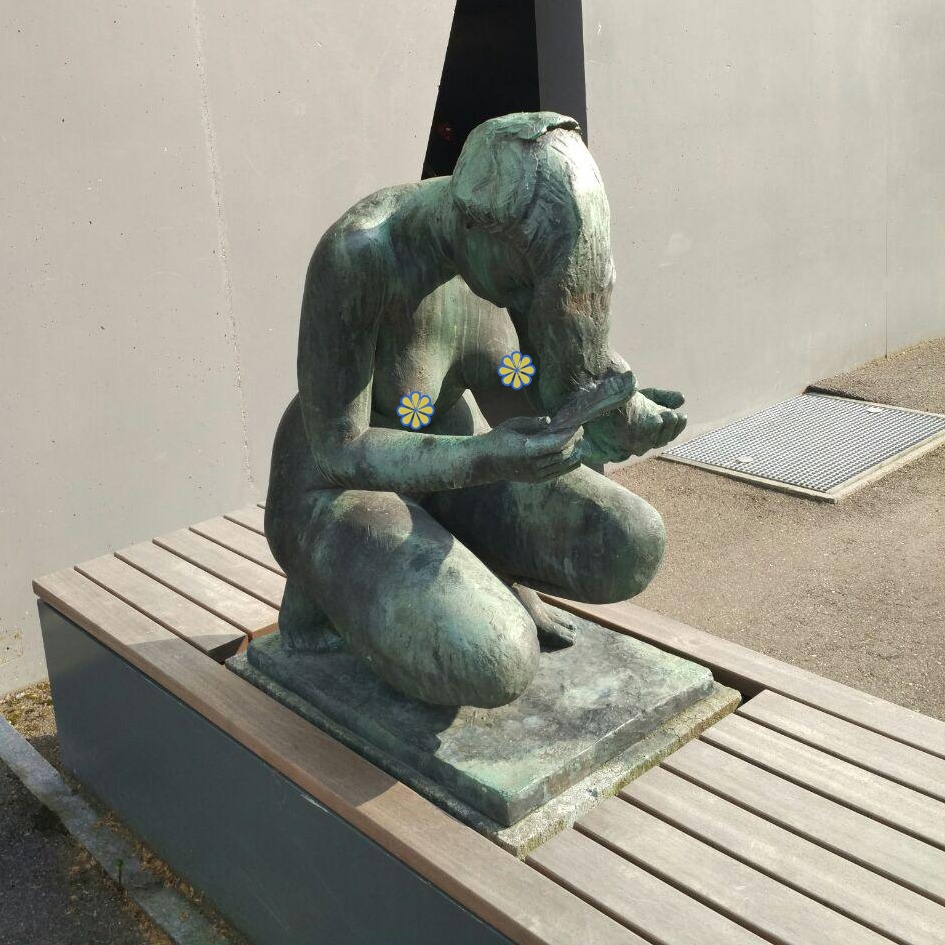

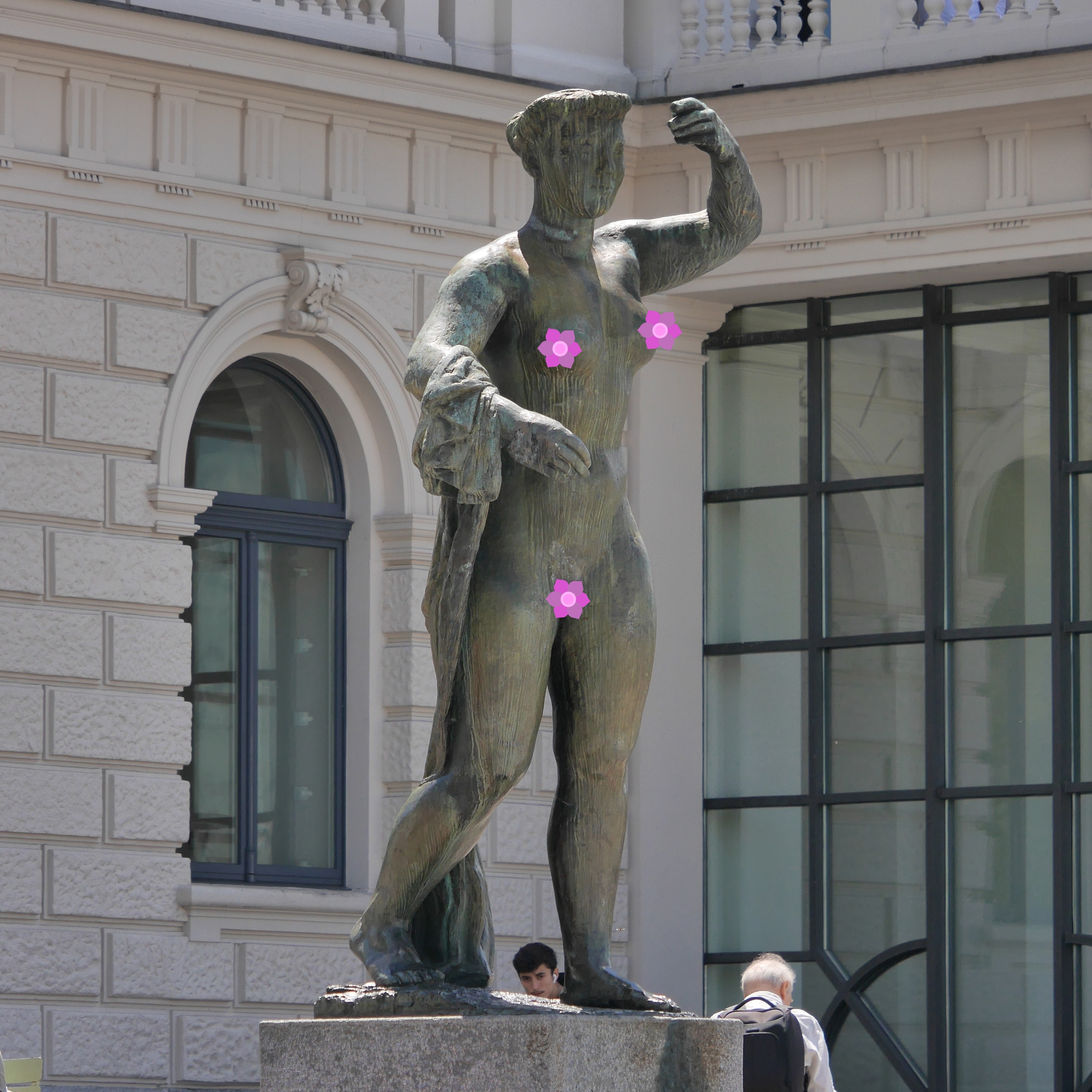

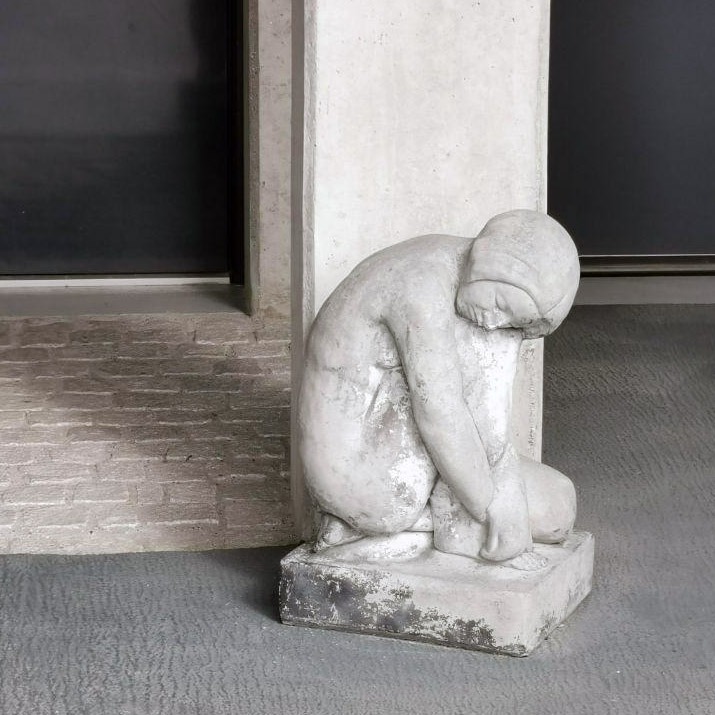

I recently moved somewhere new. Like any new arrival to a place, I was eager to explore. I set out from my rented room with an open mind and a camera. I walked and I wandered with eyes wide as saucers. Every so often I would see a statue, initially, I didn’t think anything of it. I snapped a picture and moved on. By the time I found the fifth statue I was slightly perturbed. By the time I found the tenth, I suddenly asked myself, “Why is this city filled with statues of naked women?” You may think that 10 is not such a large number in a big city. But this is not a big city. So 10 is getting to be quite a lot and I continue to see more every day. I then asked myself why I had seen so many statues of naked women, but no statues depicting naked men. This got me thinking.

Every time I see a person used in artwork it is almost always a woman. And in my experience, she is usually in either a state of undress or a sexualised pose of some sort. Do the people who create this art lack imagination, or do they think the female form is such an epitome of beauty they feel they can’t produce any other image. Frankly, if I were a man I’d be insulted. I wouldn’t be bothered if the representation of naked bodies in art and the media was half and half. If there were the same amount of artworks of men in sexy naked positions. But outside the classical stuff, there isn’t very much representation of men’s bodies in art. Opinions have changed since the olden days and women are now accepted in many roles and ways that they weren’t before. But the idea of women as beautiful objects has not been shaken free just yet. Don’t get me wrong, I can appreciate a compliment, but when the majority of representations of my sex are sexy (and naked) then I begin to wonder why I bother cultivating my mind when I would probably get further by striking an alluring pose.

The statues I found (and still find) are women as objects to be looked upon but not to be considered as real beings. The flowers I have imposed upon them are acting as a piece of tongue-in-cheek, as a nod to how it’s ok for certain body types and parts to be represented in particular types of media while others are not. They all (almost) look the same, they have very similar body types and are all suitably elegant and feminine. They are the slim woman with gentle curves, still sexy but with perfect child-bearing hips. I get that for some people, looking at naked women is nice, but why are there naked women EVERYWHERE? Why is this nudity of women necessary? The statues are not making a point, they’re just showcasing that it’s titillating to look at a certain type of female body as something to passively consume. The statues made me consider the representation of women in media and art and what that means for us as people who have to consume this art every day.

I’ll begin with a fact from the Guerrilla Girls. In the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, 85% of the nude images in the modern art section are of women. The artists? Only 5% are women. “This makes the constructed image a male-dominated and active view, thereby creating the female (who is predominately the subject in the image) as a passive object to be looked upon. The viewer sees the images through the eyes of the heterosexual male behind the camera, and from there learns to see women as objects to be consumed.” Because of this disparity, we learn to look at ourselves as objects too. We develop an intense awareness of our outward appearance. We look at ourselves from the third person and compare ourselves to the perfect images we can only see as ‘real’. These visual representations are in our psyche too. I’m sure many people will have seen the viral video ‘How the Media Failed Women in 2013’. It showcases presenters and media outlets who can’t think of anything clever to say against the arguments of the women in front of them. So they resort to insults about the woman’s appearance or gender. Usually breezing over the abilities or achievements they’re supposed to be discussing.

I learned about a website called Code Babes. It teaches people (men) how to code with the helpful addition of a female model taking her clothes off with each lesson. I learned about a series of adverts created by Veet called ‘Don’t risk dudeness’. For real. Thankfully they were not on TV for long. Apparently, women came up with this concept. I’m not surprised really, we shame ourselves and others when we don’t meet the ideal representation of what a woman ‘should’ be. We see the perfect representations in media and art and berate ourselves for not being perfect too. “So much of the female body that we see is pushed up, pinned down, sucked in, tucked in and airbrushed. Its only presentable state is when it’s altered, and so when we look at ourselves in the mirror (naked, untucked and vulnerable) we say that ‘my body must be wrong.’” All of a sudden, taking care of yourself becomes a discipline of self-surveillance. Images of ‘empowered’ women in the media come laden with messages and obligations of beauty. Obviously, this is going to affect self-confidence in women which then fuels the need for external sources of approval.

Women’s bodies are on graphic display all the time, yet they are simultaneously censored. Poet Rupi Kauer created a series of photos depicting a story of what happens during a normal menstrual cycle and posted one of the images to her Instagram account. This photo was deleted by Instagram’s censors, not once, but twice. The photo was real and was therefore deemed inappropriate. We are continuously told that it’s ok for women’s bodies to be plastered everywhere as long as they are sexy and feminine about it. Another woman, Samm Newman, found her entire account was deleted after she posted a photo of herself standing in front of a mirror in her bra and pants. Nothing was on show, no nipples or pubic hair, nothing risque. Her Instagram account was deleted because she posted a photo showing a body that did not conform to what the media tells us we should be aiming for. #notbuyingit

But beauty wasn’t always the ultimate goal for women. Up to the latter half of the 19th century, representations of women were reduced to their role within domesticity and the family unit. Their duty was simply to make babies and be a good mum. When the industrial revolution came along, suddenly women were a part of the work-force and they were removed from their isolated position within domesticity. To compensate for this loss of the maternal, physical beauty became more important when considering what it means to be a woman.

“[…] physical beauty is the reference of what a woman not only should look like, but also be like, as one’s personal look requires certain acts of behaviour to authorise it. Consequently, being a woman implies, according to the present discourse of gender identity, that one must be beautiful […]”

Not only do certain behaviours define us as proper women, but also the objects that we consume. It is through this objectification that certain products are viewed as essential parts of our personal development. “[…] the very act of consumption becomes an actual life choice, an individual choice that constructs personal identity.”

But we’re taking back control. Representations of women and feminism abound today and are taking ownership of the very same derogatory language levelled against us. We are using the insults and using them as a weapon with which to fight injustice. Examples that spring to mind are The Guerrilla Girls, the book Basic Witches, Lady Parts Justice (now know as Abortion AF), etc. These names are a way of poking fun at the insults, to show how childish they are but to also show that these words can’t hurt us. A crucial function of this is to show other women that they don’t need to be scared or ashamed because there is a whole group of people just owning it.

It’s not just names, it’s the visual representations too. Feminist photographer Liora Baker has a feminist photography series that shows real women’s naked bodies with feminist slogans written on them. By showing naked women in real terms as real bodies as real and engaged people, not objects, feminism is reclaiming the image of the woman. We are disturbing the norm with jarring images of real women with real thoughts. We are out in force proving to the world that perhaps we’re not just objects after all.

P.S. Shout out to Hannah McGregor and her podcast Secret Feminist Agenda for inspiring this essay.